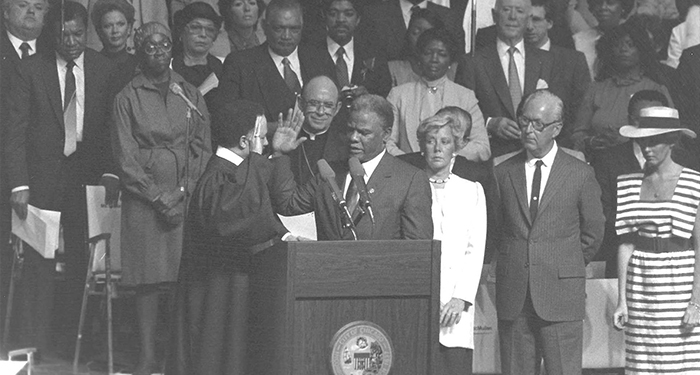

On April 29, 1983, Mayor Harold Washington was sworn in as the first African American Mayor of Chicago by Charles E. Freeman, Justice of the Appellate Court of Illinois. The inaugural ceremony was held at the Navy Pier. (Source: Chicago Public Library Special Collections and Preservation Division)

The following is a guest blog post by former Mayor Washington administration members Kari Moe and Robert Giloth.

Countless numbers of people remember precisely where they were the day Harold died. This is one measure of his profound and enduring legacy. Harold’s memory is imprinted on our psyche. Thirty years ago seems like yesterday.

Harold’s courage stands out for us. Born in 1922, Harold Washington experienced the Depression and brutal segregation on the streets of Chicago. He served in World War II, only to return to Jim Crow policies of separate and unequal. A gifted speaker and leader, he became the President of his Roosevelt College (now University) senior class in 1948, participated in Civil Rights sit ins and demonstrations, and became one of the first African-American law students at Northwestern University. Harold accomplished many “firsts” of his generation as he fought for equality and confronted the barriers of racism in America.

Elected to the Illinois legislature in 1964, Harold emerged as an independent and skilled legislator. The Chicago political machine labeled him a maverick, but he stood up to them and won re-election on his own terms, leading to successful service in the Illinois Senate. Ultimately he won the seat to represent Chicago’s First Congressional District in the Congress in 1980.

When Congressman Harold Washington took the stage to challenge States Attorney Richard Daley and Mayor Jane Byrne in the1982 Mayoral primary debate, it was less than 20 years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. Harold’s Mayoral campaign was fueled by defiance against decades of oppression by the Chicago political machine. His speeches—during his campaign and his mayoralty—called out the damaging legacy of racism in Chicago. He promised to “stomp on the grave” of machine patronage.

His campaign was also energized by Chicagoans’ hopes for a fairer city and more opportunity for their children. As Harold was fond of saying, “No corner of Chicago will be safe from my fairness”. His vision was considered radical.

The campaign against Harold was a no-holds-barred racist campaign, including leaflets depicting him as an animal, among other hateful epithets and images. His opponent’s slogan was “Epton: Before It’s Too Late”. Harold withstood these attacks, and built a shrewd, multi-racial grassroots campaign that catapulted him to the 5thFloor of City Hall.

Harold governed with the courage of a reformer well ahead of his time. He was committed to diverse representation in his Cabinet appointments, which he achieved. He set up a Mayoral Advisory Committee on Gay and Lesbian Affairs, and worked actively to build bridges with the Latino, Asian American and Arab American communities. His budget distributed funds and programs throughout the city to long-neglected neighborhoods.

Harold stood up to his enemies in the City Council, and fought for neighborhood interests to be balanced against the demands of downtown developers. He stood steadfastly for fairness and redistribution in jobs, appointments, budgets and contracts, against great opposition. Every day was an exercise of Harold’s courage.

On this anniversary of Harold’s death when we remember the exact moment of heartbreak, we remain inspired by his vision and love for Chicago. From President Barack Obama to the thousands of people who stood for hours in the cold rain and wept while waiting to pay their last respects, Harold changed his city and our lives for the better.

What does this moment call on us to do? We imagine Harold would remind us that each era calls us to be courageous in the face of oppression. He would tell us that the right to vote and democracy are precious institutions we must protect and expand. He would call on us to speak for justice, and raise young leaders to carry his work forward.

Let’s work to honor Harold’s memory by continuing his work far into the future.

About the Authors: Kari Moe served in Mayor Washington’s administration in various positions including Deputy Commissioner for Economic Development, Chief of Staff to the Development Subcabinet and Assistant to the Mayor for Community Services. She was the Director of Research and Issues during the 83-83 Mayoral campaign. Robert Giloth served as a Deputy Commissioner for Economic Development.