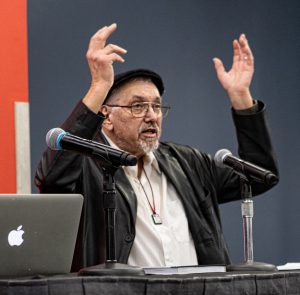

Image Source: Alan Berner, The Seattle Times

Beth Gutelius, research director of the Center for Urban Economic Development at UIC and senior research specialist with the Great Cities Institute at UIC, spoke to the Seattle Times about the use of automation and robotics to increase the pace of work in warehouses and the risks it poses to employees.

“There are many technologies that could take out some of those risks, lower the risks [and] the hazards of being a warehouse worker,” she said. “The problem is the choices the employers are making … are canceling out all those opportunities.”

“For all of the talk about how technology is changing warehousing … it’s at a much earlier phase overall in the industry than I think a lot of people assume given the news, especially about Amazon,” she said.