Teens and young adults discuss with federal, state and local officials the correlation between the city’s violence and the lack of youth employment opportunities. This program was recorded by Chicago Access Network Television (CAN TV).

Abandoned in their Neighborhoods: Youth Joblessness amidst the Flight of Industry and Opportunity

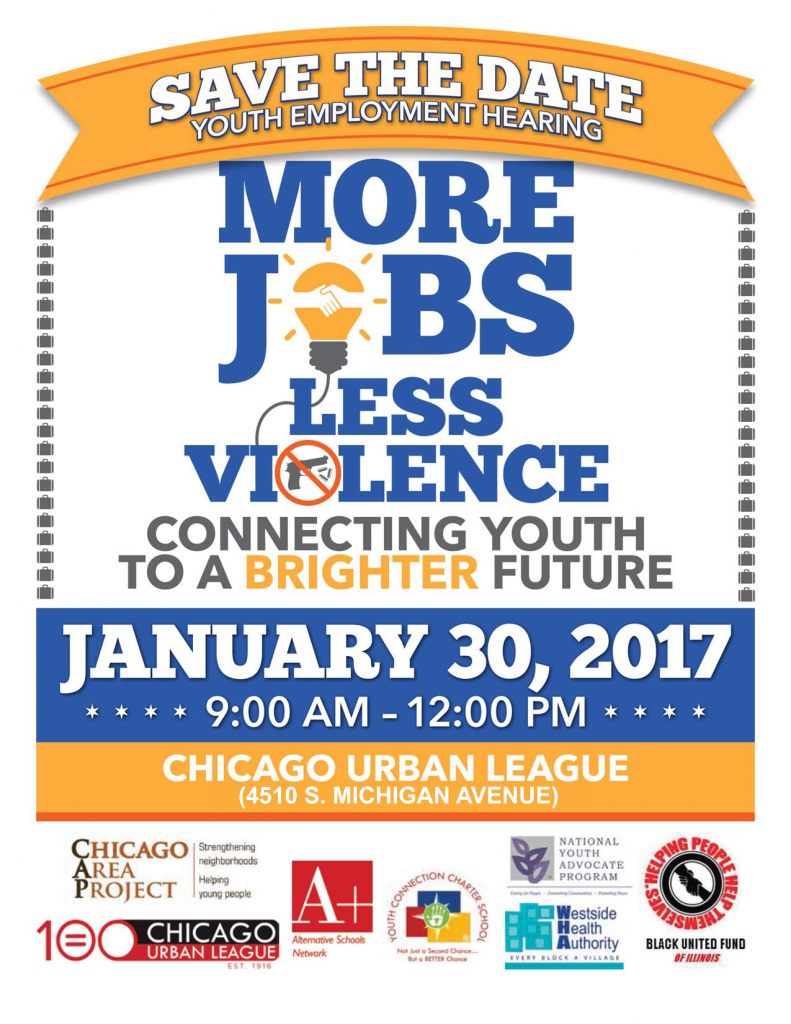

On January 30, 2017, we had the great honor to present our report on youth joblessness at a hearing organized by Alternative Schools Network (ASN) and held at the Chicago Urban League. Co-sponsors of the forum included Chicago Area Project, Youth Connection Charter School, Westside Health Authority and Black United Fund of IL, National Youth Advocate Program, La Casa Norte, Lawrence Hall, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Heartland Alliance, and Metropolitan Family Services. Among the elected officials that were present, and in some cases spoke, at the hearing were U.S. Senator Dick Durbin, Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky, Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, and several members of the Illinois State Assembly, Cook County Commission and Chicago City Council. Also in attendance was Andrea Zopp, Deputy Mayor, Chief Neighborhood Development Officer and Chicago City Clerk, Anna Valencia.

Most critical to the hearing, was the large presence of young people, several of whom participated in a panel discussion moderated by Susan Richardson of the Chicago Reporter. Shari Runner, CEO of Chicago Urban League welcomed everyone and Jack Wuest, ASN, facilitated the movement through the various segments of the hearing, which was titled, More Jobs, Less Violence: Connecting Youth to a Brighter Future.

The Great Cities Institute 2017 report, Abandoned in their Neighborhoods: Youth Joblessness amidst the Flight of Industry and Opportunity, supplements the voices of young people who have come forward at previous ASN hearings to speak about their appreciation for opportunities to work and the value they place in having a job. They have also repeatedly made the connection between conditions of joblessness and violence and that an answer to stop violence is to “get us off the streets and into some work clothes, and you will see the change.”

In our 2016 reports, Lost: The Crisis of Jobless and Out of School Teens and Young Adults in Chicago, Illinois and the U.S. and A Lost Generation: The Disappearance of Teens and Young Adults from the Job Market in Cook County, we brought attention to the issue of joblessness among 16 to 24 year olds by examining employment to population ratios, joblessness and out of work/out of school rates comparing whites (non-Hispanic), Hispanics or Latinos and Blacks (non-Hispanic) within Chicago and between Chicago, Illinois, the U.S., Los Angeles and New York. The figure that nearly half of black 20 to 24 year old men in Chicago were neither working, nor in school, sent shock waves about the severity of the joblessness problem that our GIS generated maps showed were most severe in neighborhoods with the highest concentrations of blacks, and then Latinos. In our conclusions, we asserted that the joblessness problem could not be understood without understanding the conditions of the neighborhoods themselves.

In our 2017 report, we wanted to investigate further our conclusion that joblessness was chronic and concentrated and we wanted to know more about the conditions of the neighborhoods. Based on our data, we conclude:

- Joblessness among young people continues to be disproportionately felt by young people of color, especially black males;

- Joblessness among young people is chronic and concentrated;

- The recession made conditions worse and that for some, recovery is either slow or nonexistent;

- Joblessness among young people is tied to long term trends in the overall loss of manufacturing jobs; and most notably,

- Joblessness among young people is tied to the emptying out of jobs from neighborhoods, which is in contrast to jobs that are being centralized in Chicago’s downtown areas where whites are employed in professional level services and blacks and Latinos in service retail.

We learned from the report that “many neighborhoods in Chicago are economically abandoned sectors with a dramatic loss of industry and opportunity for employment. These neighborhoods have been abandoned, along with the people that live there.”

Joblessness persists, is part of a long-term trend made worse by the recession, and is directly tied to the flight of industry from neighborhoods. Manufacturing was particularly important in Chicago and when it declined, Chicago workers were hard hit. As an example, in 1960, sixty percent of the 20 to 24 year-old Latino labor force was in manufacturing. By 2015, that number had dropped to ten percent. Joblessness, we conclude, is systemic and is directly related to structural changes in the economy.

Understanding that residential segregation and economic and occupational restructuring is the structural context for what is happening to our young people of color, is a pointed reminder that chronic and concentrated youth joblessness must be understood in terms of its structural roots and not as a function of individual attributes. Blaming young people for their plight does nothing to remedy their conditions. Providing structured opportunities for employment and capacity building does.

We conclude the report with four categories of strategies to tackle chronic and concentrated joblessness.

- Create direct employment opportunities

- Reinstate federal, state, and local summer jobs programs

- Replicate New Deal strategies

- Fund paid mentorship programs

- Create apprenticeship programs

- Recreate employment subsidy programs

- Prepare young people from affected neighborhoods for the livable wage jobs that do exist and equip them to participate in the emerging economy

- Increase public education expenditures

- Provide on-the job training

- Expand training and workforce development

- Remove the impediments to employment, including those related to criminal records

- Revive economically abandoned neighborhoods

- Attract anchor employers that hire neighborhood residents

- Assist and incentivize small business development

- Create incentives for venture capital investments that are not totally predicated on immediate profit recovery

- Enhance conditions for community led initiatives such as worker cooperatives and small business incubators that harness the skills and talents of young people, both of which can become the basis for revitalized commercial districts to supply the much-needed access to a wider range of goods and services

- Increase funding for community organizations that provide mentorship and capacity building of young people

- Stop the bleeding of job loss and reverse policies that reward extraction of wealth from communities

- Tie tax incentives for corporations to actual job generation, which are then monitored for adherence to agreements with penalties for non-compliance

- Accelerate incentives to investments in neighborhoods and evaluate their effectiveness

We came to this issue because we recognize the significant consequences of joblessness among young people. Throughout the process of producing and presenting this report, we have had the opportunity to meet young people, many that work with them and an array of elected, civic and community leaders. Without question, the young folks themselves are talented and intelligent and their mentors are dedicated and engaged in efforts that make a difference. With the many phone calls, conversations and invitations that we have received since we released last year’s and now this year’s reports, we are heartened to see so many express their concern and their efforts or willingness to be part of the solution. It is indeed an honor, to provide data and analysis that contributes to these efforts.

Both the Executive Summary and the Full Report are available. The full hearing can be viewed, thanks to CAN TV. In addition, you can also see the link to the various media that have covered the report.

Chicago Tribune: Report says youth unemployment chronic, concentrated and deeply rooted »

Chicago Tribune: Fix Chicago’s violence? Start by helping kids land jobs »

Crain’s: New report details huge unemployment among young blacks, Latinos in Chicago »

Youth Employment Hearing

Report says youth unemployment chronic, concentrated and deeply rooted

Toni Ross works at Food and Paper Supply Co. on Jan. 27, 2017, in Chicago’s Grand Crossing neighborhood. Ross has worked at the food service distributor for 27 years; she was hired through a youth program and is now store manager. The business’ co-owner is slated to speak at a forum on youth unemployment Jan. 30, 2017. (Phil Velasquez / Chicago Tribune)

An article from the Chicago Tribune highlights a new report from Great Cities Institute and commissioned by Alternative Schools Network for a January 30, 2017 hearing on youth joblessness at the Chicago Urban League. The report finds that youth unemployment is chronic, concentrated and deeply rooted.

Chicago is making scant progress in its ongoing battle against rampant youth joblessness, new statistics show, though there is a modicum of good news.

The share of 20- to 24-year-old black men who were neither working nor in school declined modestly between 2014 and 2015, from a dismal 47 percent to a still-dismal 43 percent, according to a report set to be presented Monday at the Chicago Urban League’s annual forum on the youth unemployment crisis.

Abandoned in their Neighborhoods: Youth Joblessness amidst the Flight of Industry and Opportunity

Executive Summary:

“More Jobs, Less Violence: Connecting Youth to a Brighter Future,” is the title of the 2017 Youth Employment Hearing sponsored by Alternative Schools Network and held at the Chicago Urban League on January 30, 2017. Other co-sponsors of the hearing include Chicago Area Project, Youth Connection Charter School, Westside Health Authority, Black United Fund of IL, National Youth Advocate Program, La Casa Norte, Lawrence Hall, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Heartland Alliance and Metropolitan Family Services. Each of these groups work directly with young people, providing mentorship and employment related opportunities. Elected officials from federal, state and local government attended to hear the data presented and the voices of young people who testified on their experiences related to employment. This report, produced by UIC’s Great Cities Institute, provides a supplement to the voices of the young people and those that work with them.

Authors:

Teresa L. Córdova, Ph.D.

Matthew D. Wilson

Executive Summary

Full Report

Presentation Slides

Behind sale of closed schools, a legacy of segregation

(Photo by Max Herman)

Key Elementary School, located in the predominantly black Austin neighborhood, has stood empty since 2013 when it became one of 50 under-enrolled Chicago public schools shuttered to save money.

A report on school closures by Great Cities Institute Research Fellow and Professor of Urban Planning and Policy, Rachel Weber and fellow authors, Stephanie Farmer, Associate Professor, Sociology Department, Roosevelt University and Mary Donoghue, ULI-Trkla Scholar at the Great Cities Institute was highlighted in an article from The Chicago Reporter

The school closure issue, like so many issues in Chicago, is rooted in racial segregation and its consequences. A new study released by the Great Cities Institute at the University of Illinois at Chicago that looked at school closures and turnarounds between 2000 and 2013 found that race, not simply enrollment or academic performance, was a recurring factor. Schools that were predominantly black and located within six miles of the city’s center, where there is more redevelopment potential, were more likely to be turned around or closed.

Although the school district chose “race-neutral” metrics to justify the restructurings, the report argues that they interacted with “institutionalized racial inequities” and had outcomes that disproportionately affected black students.

The report states: “Legacies of racism—from the broader interactive effects between de jure and de facto residential segregation and labor market discrimination to prior CPS plans and practices like the fact that the district often built new schools rather than redraw boundaries that would put black and white students in the same schools—shape contemporary capital investment policies in Chicago.”

Engineered Conflict: School Closings, Public Housing, Law Enforcement and the Future of Black Life

News Briefs from the Holidays

- An article from Financial Times on the economic and opportunity gap between different areas of Chicago features comments on gang violence from John Hagedorn, UIC professor of criminology, law and justice, and unemployment data from an earlier report produced by UIC’s Great Cities Institute. Full Story »

- Findings from an earlier UIC Great Cities Institute report on joblessness in Chicago were cited during “The View From My Block,” a call-in special from WBEZ-FM and WVON-AM that examined causes and solutions to Chicago’s gun violence. Full Story »

- DNAinfo Chicago quotes Jack Rocha, a research specialist at UIC’s Great Cities Institute, in an article about a beautification plan for the Calumet River that calls for more public green space. The South Chicago Chamber of Commerce is currently working with the institute to develop a commercial corridor revitalization plan that incorporates citywide efforts to improve recreation offerings along Chicago’s rivers. Full Story »

- Findings from an earlier UIC Great Cities Institute report on unemployment in Chicago are cited in a USA TODAY article about the city’s crime levels and policing strategies. Full Story »

Explaining School Closures: A Report by Rachel Weber, Stephanie Farmer, and Mary Donoghue

We hope that you had a blessed holiday season. We know that this new year brings with it many challenges and responsibilities. Simultaneously, we embrace opportunities to harness the power of research to suggest solutions to today’s urban challenges. Often, we must first analyze policies that create or exacerbate those challenges. A much talked about policy in the City of Chicago, was the closure of public schools. While some may have denied that there was any significant impact, there was much conjecture and anecdotal information that suggested that the decisions to close these schools was disproportionately felt in those neighborhoods that could least afford the loss of an anchor institution. Great Cities Institute Research Fellow and Professor of Urban Planning and Policy, Rachel Weber and fellow authors, Stephanie Farmer, Associate Professor, Sociology Department, Roosevelt University and Mary Donoghue, ULI-Trkla Scholar at the Great Cities Institute took on the task of assessing whether and how an array of multiple factors affected the decisions to close schools.

Here is a brief abstract of the report and below is a link to the report itself. We offer this, of course, to keep fresh, the importance of public schools in serving Chicago’s neighborhoods and their families.

Our study sheds light on the multiple, often conflicting interests that school districts must balance to plan for the capital needs of school-age populations. We investigate the factors that led to the closure of public schools in Chicago between 2000 and 2013. We reverse engineer the school closure decisions under two mayoral administrations by constructing a logit model that estimates the decision to close schools that were open as of 2000 as a function of physical, student, geographic, political, and neighborhood demographic factors.

Our findings reveal that building utilization and student performance were predictors of these closures, but so was the race of students in each school. Specifically schools with larger shares of African American students had a higher probability of closure than schools with comparable test scores, locations, and utilization rates.

Whether administrators explicitly considered the race of a school’s students in planning decisions or whether race in our model was a proxy for other unmeasured characteristics, the cumulative effect of technical decisions interacting with a racially differentiated education environment forced African American students and their families, to bear the burden of these administrative disruptions.

Why these schools? Explaining school closures in Chicago, 2000-2013

Authors

Rachel Weber, Ph.D.

Stephanie Farmer, Ph.D.

Mary Donoghue

Abstract

Our study sheds light on the multiple, often conflicting interests that school districts must balance to plan for the capital needs of school-age populations. We investigate the factors that led to the closure of public schools in Chicago between 2000 and 2013. We reverse engineer the school closure decisions under two mayoral administrations by constructing a logit model that estimates the decision to close schools that were open as of 2000 as a function of physical, student, geographic, political, and neighborhood demographic factors. Our findings reveal that building utilization and student performance were predictors of these closures, but so was the race of students in each school. Specifically schools with larger shares of African American students had a higher probability of closure than schools with comparable test scores, locations, and utilization rates. Whether administrators explicitly considered the race of a school’s students in planning decisions or whether race in our model was a proxy for other unmeasured characteristics, the cumulative effect of technical decisions interacting with a racially differentiated education environment forced African American students and their families to bear the burden of these administrative disruptions.